On Colonus

Morgan Mandalay

January 18 - February 22, 2020

@

Extase

Chicago, Il

By Gareth Kaye

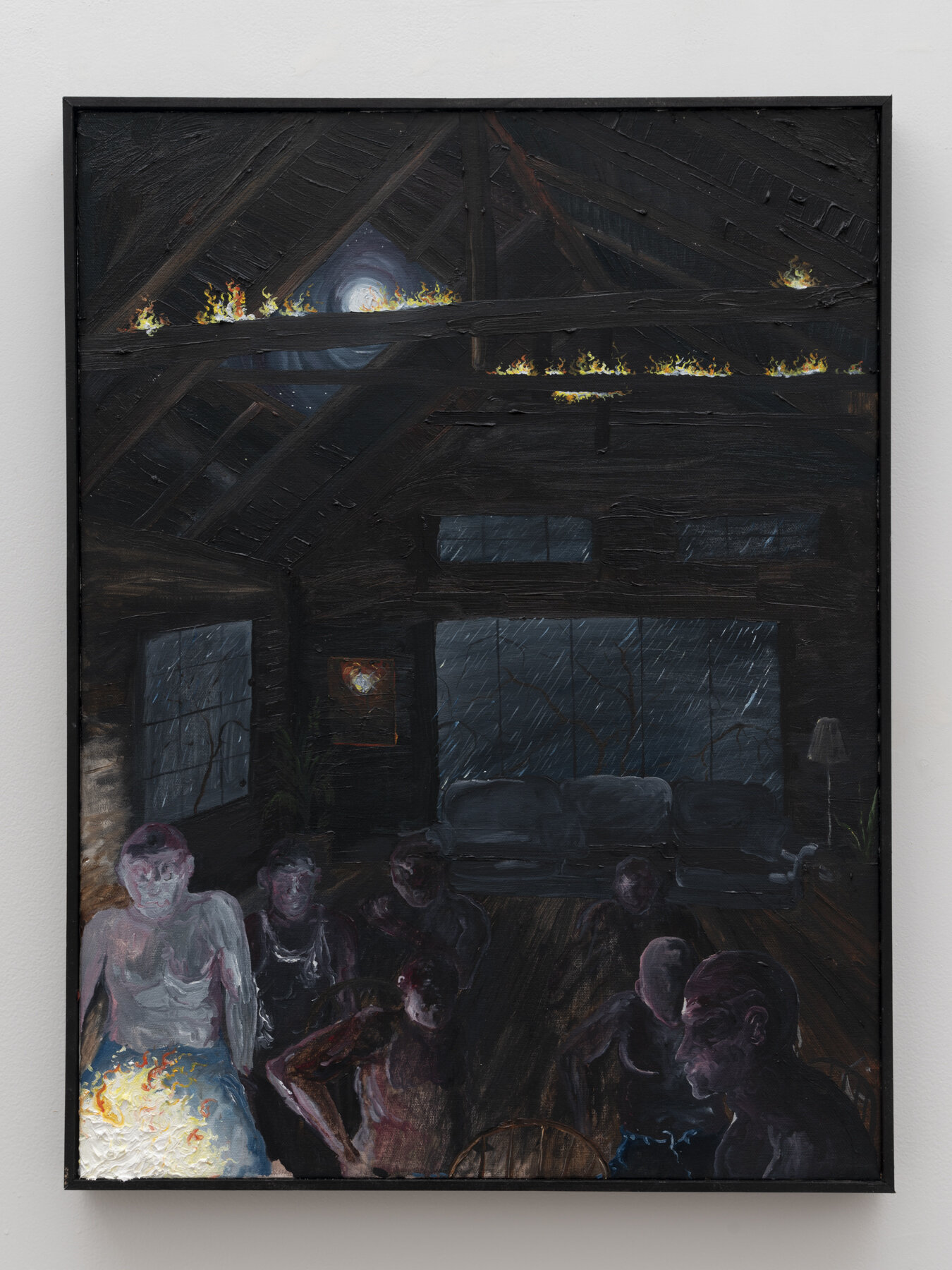

Undifferentiated figures huddle for warmth around a fire in modern, well-furnished log cabin. There is a storm out, the rafters have started to catch fire too, but no one – the architecture included – seems too fazed by it. Memory Palace is one of six paintings by Morgan Mandalay in his latest solo exhibition On Colonus which is currently on view at Extase, an apartment space in Chicago’s Ukranian Village neighborhood. It takes its title from the second play in the Oedipus Rex trilogy, Oedipus at Colonus, a story of vengeance, redemption, and a search for a safe place to call home. Mandalay’s augmentation from ‘at Colonus’, to On Colonus can be interpreted as either a treatise on the tragedy’s themes of catastrophe, searching, and hope; or as a literal declaration of perspective: ON Colonus, a surveying view taken from the top of the rubble and disaster, a lookout’s view to find a safe haven from the inhospitable landscapes and interiors we are presented with.

Mandalay’s paintings are of a not so distant future, perhaps they are even of a vague present. Stray flames flicker in thick gooey impasto off the canvas. The images tug and chase themselves from immaculately rendered, to expressionistically hinted at objects and surfaces. When there are figures, they are for the most part equally featureless with the same scorched, swirling and leathered skin, they are bodies marked by their exposures to trauma – be it in memory or their present environment – not unlike Oedipus. Their bodies are reposed, relaxing in a relatively consistent uniform of shirtlessness, blue jeans and white tube socks (a distinctly American uniform) amidst the storms and flames outside, either ignoring or coping, the line between the two remains ambiguous.

Installed alone in the recess of a small closet – which gives the painting an air of the sacred – In the Garden of Hesperides shows a burnt looking figure wanders through a darkened grove of lemon trees, evinced by the yellow fruit visible in the foliage above. They are shirtless, jeans rolled up, a straw hat on their head, tube socks peering out of the tops of their boots and walking stick in hand. Their eyes downcast, watching carefully where they tread. The man’s implied blindness or visual impairment is suggested either by the walking stick, scant luminescence offered by the moon and flames flickering in the foreground and of course the evocation of Oedipal tragedy throughout the exhibition. the fruit give ways to piercing blue eyes staring through the firmament like the opening credits of a Scooby-Doo episode at both the figure and viewer.

In classical mythology, the Hesperides were nymphs of the night, living in resplendent gardens and associated with the protection of sacred golden apples. In this case, Mandalay has incarnated the apples as lemons, a recurring actor is in his work, and something of a metonym for loss, confusion, for something potentially refreshing becoming sour. While considering his prior paradisiacal paintings and the contrast they present to the tempestuous environs of the exhibition at hand, the adage of “when life gives you lemons…” (you know the rest) slipped into my head and stuck there as I thought image’s relationships to both their namesake tragedy and the world at hand.

The impetus of the saying is perhaps no clearer than in Aug 1961, In the Dark. The view is constructed from the position of the owner of an arm entering the image the plane, flicking a light switch. Above the switch is a picture pinned to the wall of a family in front of a car, an inscription on the image’s white border reads “Aug 1961.” This is a specific kind of picture, ubiquitous in family photo albums from. While the photograph is not painted clearly, the aura of middle-class aspiration is still deeply legible. Through the threshold the doorway afigure stands, holding a knife and lemon in hand. The moon shines through an open window, and the tree outside has caught fire.

None of the characters seem too put off by the looming flames. Are they going to flee? Is the light being turned on or off? Judging by the shirtless contrapposto of the person holding the lemon it doesn’t seem like there is any urgency. After all, isn’t the single-family home the apex of American Paradise? The atomization of familial/community unity in to discrete and reproducible forms? If you are condemned to die, why not burn in the paradise you have been prescribed to aspire to? There is a Cards Against Humanity Card that pointedly goes “Getting married, having a few kids, buying some stuff, retiring to Florida, and dying.”

Perhaps the most ignored fact about paradise is that it is generationally inherited, from the biblical “promised land” to the American Dream, and like lemons they’ve both kind of soured overtime. Paradise is much more an idea than a place, and a presumptuous one at that. In his own words Mandalay has described the exhibition saying “…a home has been built inside of paradise; a memory. In this home, I am attempting to find my place; but as memory is filled with shadows and gaps and holes, I am wandering blind attempting to construct this home and construct this narrative of myself.”

What Mandalay is proffering about Paradise may not only be its fleeting nature, but also its ineffability. It is not something you can speak into existence, rather it must be tasted. Lemonade for some is just unsweetened lemon juice for others. We have been endlessly given fleeting tastes of paradise, making us believe that if we could have a whole portion it could last forever. The world we have been given is different than it was for those who invented these paradises, though these places still maintains its draw upon our psyche their relevance is uncertain today.

Forbidden Fruit is a dreamy painting whose soft, hazy texture differs from the sumptuous layers of oil that build the bodies of most of On Colonus’s works. In it, two figures, the only ones in the show with clearly defined sexes, stand nude on either side of a lemon tree. They’re an Adam and Eve-ish type, but in this version, it is Adam who is entwined by the serpent, who feeds the man the lemon (another golden apple) with his mouth. A fatal kiss destined to exorcise Adam and his mate; who helplessly looks on in distress from behind, from paradise. In front of the male figure lay a pair of jeans and a straw hat on the ground, and a walking stick against the tree.

In fact, once the viewer takes notice of the garb strewn across the ground, the painting can develop a complex call and response to In the Garden of the Hesperides. A second, and closer inspection of this painting provokes the question of whether or not this is this “Adam’s” journey out of the garden, the eyes in the shadow watching to make sure he leaves, entering the flaming wasteland suggested in the other canvases. If this is the case, where is the “Eve” in the rest of Mandalay’s allegory? In a just paradise, she wouldn’t bare the punishment of her companion’s desire to consume more of paradise than allowed. From the transgression of Forbidden Fruit to the potential consequences of In the Garden of the Hesperides, I arrive at what reads to me as the exhibition’s final painting (it’s the closest to the exit) Signs of Life on Colonus.

Considering its immediate right-hand proximity to In the Garden of the Hesperides, I would like to imagine Signs of Life on Colonus as not only the On Colonus’s punctuation, but also as the view awaiting the figure exiting the garden. The image depicts a burning landscape. The light is a dusty orange polluted by ash and smoke. Skeletal trees flicker with flames against their spectral, ashen trunks and branches. There is a town hinted at in the distance, giving rise to the thought that the broader civilization, perhaps, might be protected from the inferno? But alas, smoke is there as well. The painting is a window to a time fast approaching, and a mirror to those who know a thing or two about living through a fire; as a native Californian, I am sure they are no stranger to Mandalay.

The paintings in On Colonus ask many questions about our relationship to home and to where we settle. Is it everything we ever dreamt, or more likely, is it just what works? Are we staying there because we were exorcised from a better place? (Forbidden Fruit and In the Garden of the Hesperides), do we love it so much that we are willing to perish there? (Memory Palace) or are we trying to keep something unsustainable going when we know it is about to start collapsing around us at any moment? (Aug 1961, In the Dark)

Nowadays it seems paradise has had all the life it promised sucked out of it. It is starved of the imagination for alternatives that should renew it and it burns in emaciation as a result. The fires signal not only it’s destruction, but also its cleansing, making way for a new landscape, and a new place to call home if those who settle thereafter can imagine one.

When I was a boy, I loved going to the mall for the free teriyaki chicken samples at Makai of Japan. I never really go to eat any more than the sample most of the time, the taste constructed a fantasy of something I aspired to consume. Paradise was in a Styrofoam box that seven-year-old me didn’t have the funds for. On special days I got to eat a whole meal of it (thanks Mom and Dad) and it was great, but I would eat it so quickly it vanished.

We burn through paradise, like the fires in Mandalay’s images do in a literal way. The paradise we were promised has been scorched by fires and oil spills, abuse, traumas, student debt, and hospital bills. Accumulating credit and bottomless consumption of resources put a loophole in space time and drained the lifeforce from our and our children’s futures to feed our parents’ and grandparents’ paradise. Mandalay paints from the vantage point of a generation of persons who are left stranded at Colonus, a land protected by the Erinyes, spirits of vengeance. Here On Colonus Mandalay leaves us with the question of whether or not we ourselves will be a fire that cleanses, or just another figure standing idly waiting to burn in comfort, but regardless of what we choose, it is finding a place to call our own through the decision making process that is the most basic expression of hope.

Morgan Mandalay On Colonus opened January 18 and runs until February 22nd at Extase and was organized by Extase director, Budgie Birka-White. Gallery hours are Tuesday – Friday 1-5pm, or by appointment. You can schedule an appointment by emailing . info@extasechicago.com

Photographer: Jesse Meredith

Copyright: Morgan Mandalay, Courtesy the artist and Extase